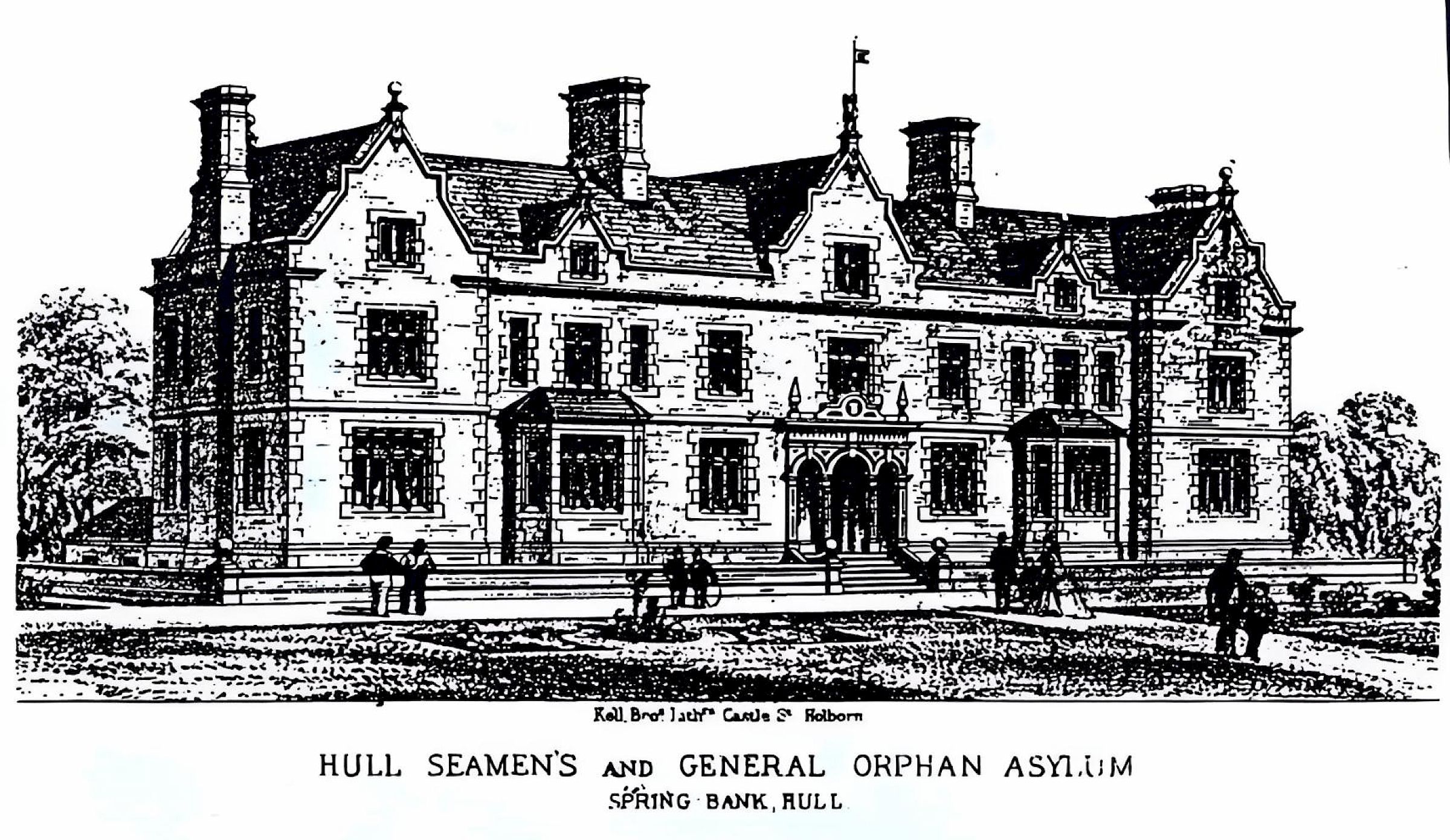

Seamen’s Orphanages

Working seamen lived dangerous and peripatetic lives which left families and dependants unprotected. Orphanages were created to provide opportunities for those left behind.

Duncan, Life in the Spring Bank Orphanage, 1

The nineteenth century maritime world was rife with calamities, reflecting the precarious nature of seafaring life. Sailors embarked on treacherous journeys, battling unpredictable weather, hostile waters, and the constant threat of shipwrecks. As ships were lost to the unforgiving sea, the lives of countless sailors were claimed, leaving behind grieving families and orphaned children. This stark reality exposed the vulnerability of families who depended on maritime trade for their livelihood.

The widows and children left behind were often thrust into poverty and destitution, grappling with grief and economic uncertainty. In a society that was yet to establish comprehensive social safety nets, these families found themselves marginalised and dependent on charitable institutions for survival. The futures of the children of the deceased became uncertain, and they often faced a grim reality of overcrowded workhouses, inadequate living conditions, and meagre sustenance.

Image: Cover of John William Duncan, Life in the Spring Bank Orphanage 1869 to 1875 (s.l: s.n., 1985). Hull Local Studies Library. Peproduced with permission.

Amidst this backdrop of adversity, free education and training emerged as a beacon of hope for sailors' orphans. Philanthropic efforts and the growth of the charity sector sought to provide these children with a chance at a brighter future. The government and the Christian church took a leading role in establishing institutions to equip orphaned children with the skills needed to escape the cycle of poverty and secure a more stable existence. Through a combination of formal schooling and vocational training, these children were given the tools to break free from the constraints of their circumstances. Subjects such as navigation, mathematics, and practical seamanship were integrated into the boys' education, acknowledging their maritime heritage while preparing them for diverse career paths.

One of the first church-based initiatives was the Sailors' Orphan Institute in Hull. It was established in 1836 in the wake of the loss of four whalers in 1836 that left 20 widows and 61 orphans, to provide clothing and education to as many of these children as possible. The boys received yearly 'a blue woollen jacket with an appropriate design on the collar, a waistcoat and a pair of trousers, two shirts, two pairs of stockings, a cap or hat and a handkerchief', and girls were given 'a blue stuff frock, a straw bonnet, a cap and a tippet'. Education was provided by the British and Foreign School, where the children ‘committed to memory Dr Watt's Catechism and Divine Songs for Children with selected portions of the Scriptures'.

Image: 'Clothing Issued Christmas 1861'. Source: J.D. Hicks, Our Orphans: The Story of the Hull Seamen's & General Orphanage 1853-1979 (Ferriby: Lockington, 1983), 7. Hull Local Studies Library. Reproduced with permission.

The institute struggled with finances and called upon the goodwill of local women to help with its activities, including making dresses for the girls. It was converted into a residential home in 1863 with 6 boys and 6 girls. The by-laws of the institution were a 'combination of Christian idealism and Yorkshire good sense' – which placed strict emphasis on discipline and religiosity. Family visit was allowed once a month, no child was allowed to spend the night outside, and all had to attend chapel conducted by the matron twice a day. When the children left the Home, they were given a bible, a painted deal box, and an outfit of the value of £2. The value of Christianity was driven into the children’s minds through verses such as the following:

My God I hate to walk or dwell

With sinful children here;

Then Let me not be sent to Hell

Where none but sinners are.Lord I ascribe it to Thy grace

And not to chance as others do,

That I was born of Christian race

And not a heathen or a Jew.

Image: 'Last Application'. Source: J.D. Hicks, Our Orphans: The Story of the Hull Seamen's & General Orphanage 1853-1979 (Ferriby: Lockington, 1983), 18. Hull Local Studies Library. Reproduced with permission.

The early attempts at relieving distress were not an unqualified success. The Hull Mariners' Church Sailors' Orphan Society's annual report from 1861 records the problems of school attendance caused by the dismissal of one child, indefinite suspension for two, and withdrawal of three children by their mothers. Girls often were absent from school as they had to look after younger children at home. The committee opened a residential home in 1866 to exert greater care and influence on the children's lives. Numbers at the school reached a peak in 1867 with 116 boys and girls on the roll. The following year, the committee decided to concentrate all its resources on the residential home. As a result, new inclusions stopped, and the number of children was reduced to 3 boys and 3 girls in 1874. The number gradually increased to 200 at the turn of the century.

Image: 'Opening of the Asylum'. Source: J.D. Hicks, Our Orphans: The Story of the Hull Seamen's & General Orphanage 1853-1979 (Ferriby: Lockington, 1983), 15. Hull Local Studies Library. Reproduced with permission.

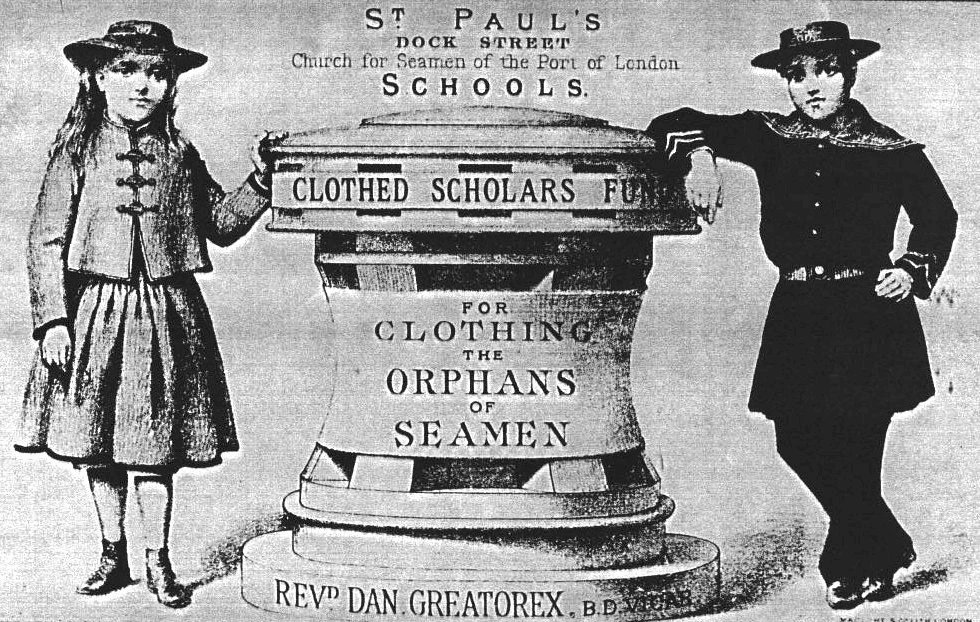

Even where the church was not responsible for running such institutions, they provided compulsory religious education to the inmates. The children at the Sailor's Orphan Girls' School and Home in London attended two Sunday services. The institution was established in 1829 for the 'board, clothing, education, and training in domestic duties of necessitous orphan daughters of the Royal Navy or Merchant Service, or the Royal Marines, or of Fishermen from all parts of the United Kingdom'. The Sunday Schools ran by St Paul's Church for Seamen in London educated on average 250 children a year, of whom about 200 were seamen's children.

Image: 'Clothed Scholars Fund'. Source: St George in the East Church, accessed 20 August 2023

In Hull, the benefactors of the charity were able to recommend names of orphans for the committee's consideration. In other places, such as the Sailors’ Orphan Girls School and Home in London, the admiralty reserved the right to nominate children as the primary funding body. In 1880, the girls sheltered by the London School included 55 elected and 26 nominated orphans. They were trained in housework such as cooking, laundry and needlework. Suitable situations as domestic servants were procured for them when they were 16. They children were not forgotten after starting employment. They could return to the Home as a temporary shelter between jobs and were given prizes for the length of service in one place.

As we reflect on this chapter of history, it prompts us to consider the impact of religious philanthropy on marginalised members of society. The sailors' orphans, caught in the crosscurrents of the sea and societal shifts, embody the complexities of an era marked by progress and hardship. Their experiences remind us of the enduring power of education in shaping lives, and the social responsibility of providing opportunities to those in need. Their legacy underscores the importance of compassion, education, and resilience in the face of life's most challenging circumstances.

Hicks, J.D. 1983. Our Orphans: The Story of the Hull Seamen’s & General Orphanage 1853-1979 (North Ferriby: Lockington Publishing Company).

Hull History Centre. Reports of the Hull Seamen’s and General Orphan Society 1865-77 (DSHO/1/57, DSHO/1/58).

London Metropolitan Archives. Sailors’ Orphan Girls’ School and Home 52nd Annual Report, 1880-81 (A/FWA/C/D/122/001).

London Metropolitan Archives. The Royal Sailors’ Orphan Girls’ School and Home 88th Annual Report, for the Year Ending 31st March, 1917 (A/FWA/C/D/122/001).

Allison, I.E. 1981.Steadfast and Sure: A History of Sailors’ Children’s Society, 1821-1979 (Hull: Sailors’ Children’s Society).

Duncan, John William.1985. Life in the Spring Bank Orphanage 1869 to 1875 (Hull: Malet Lambert Local History Originals vol 26).

Mitchell, Charles, 1961. The Long Watch: A History of the Sailors’ Children’s Society 1821-1961 (Hull: Sailors’ Children’s Society).

Manikarnika Dutta, 'Seamen’s Orphanages' Mariners: Race, Religion and Empire in British Ports 1801-1914, https://mar.ine.rs/stories/the-church-and-sailors-orphans/

Retrieved 19 May 2024