British Sailors

During the 1800s, British sailors, along with many European sailors from Scandinavia and the Baltic, were essential to Britain's marine industries. Despite facing dangerous working conditions, language and cultural challenges, these seafarers significantly contributed to Britain's maritime dominance in a time of booming coastal and global trade and exploration.

Source: Henry Herbert La Thangue, A Mission to Seamen (1891), Nottingham City Museums & Galleries.

Britain emerged as the world’s leading maritime empire in the late eighteenth century. The Royal Navy and the Merchant Marine were integral to its imperial supremacy. The Royal Navy employed British seamen who provided invaluable service in conquering territory, securing new markets, safeguarding trade routes, and constructing a national and imperial identity. Merchant seamen, who worked in the commercial fleet of cargo and passenger ships, were a vital resource for their role in putting the policies of mercantilism and free trade into operation and enriching the empire.

Historians have acknowledged that these seamen’s impact on British imperialism extended beyond defence. As historian Stephen Gray (2018) has argued, they influenced ‘labour forces, indigenous societies, imperial networks, and imaginations of empire.’ These seamen constituted a wide variety of professionals such as mates, midshipmen, quartermasters, boatswains, able and ordinary sailors, apprentices, surgeons, stewards, cooks, carpenters, sailmakers, engineers, firemen, and stokers, not to mention ship commanders and officers, and even fishing professionals.

In spite of their important role, seamen were poorly paid and had the reputation of being rootless, often violent, promiscuous, and dipsomaniac. Their wild and noncommittal character entrenched itself so deeply in popular imagination that many accounts of maritime life, fictional and nonfictional, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries described them as inveterate troublemakers. Usually conscripted at a young age from working class households, forced into the hostile environment of ships and unknown regions, and given irregular wages and low-quality food, the sailor was an endangered and often disgruntled person.

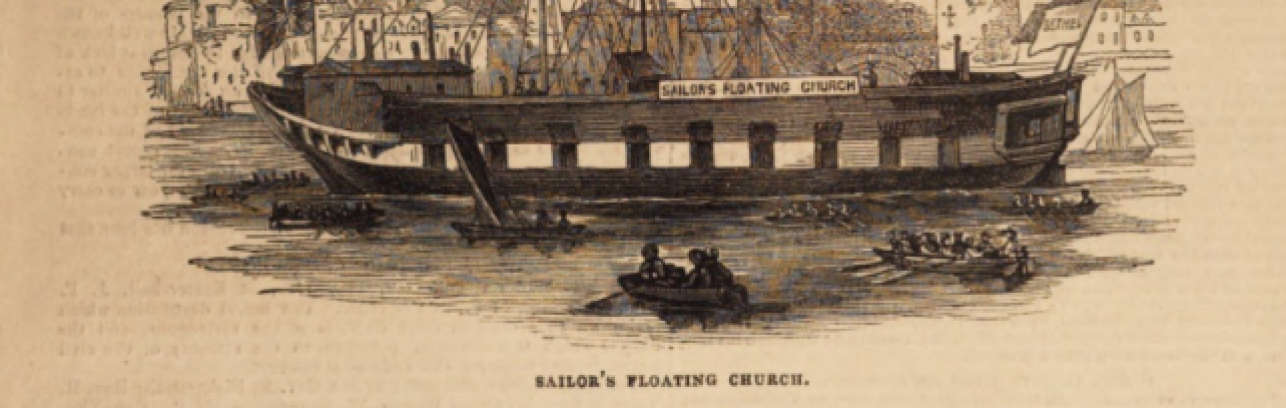

This strand will examine the role of maritime religious missions and charities who sought to improve the moral and material wellbeing of British seamen and their families. Its primary focus will be the work of charitable institutions in Bristol, Hull, Liverpool and London in the nineteenth century.

Gray, Steven. 2018. Introduction. In: Steam Power and Sea Power: Coal, the Royal Navy, and the British Empire, c. 1870-1914 (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

Kverndal, Roald. 1986. Seamen's Missions: Their Origin and Early Growth (Pasadena, CA: William Carey)

Miller, R.W.H. 2012. One Firm Anchor: The Church and the Merchant Seafarer, an Introductory History (Cambridge: Lutterworth)

Manikarnika Dutta, 'British Sailors' Mariners: Race, Religion and Empire in British Ports 1801-1914, https://mar.ine.rs/who/europeans/

Retrieved 19 May 2024

Timeline Filter

Where Filter

Who Filter

What Filter